As B.B. Warfield put it, Reformed theology is “Christianity come into its own”, and the EPC should happily and clearly communicate that along confessional lines. There are important things that distinguish the EPC from the PCA, but our doctrine is not one. If we are going to contrast ourselves with other Christians, we should do so by emphasizing our confessional system over and against broad evangelicalism. The EPC is no minimalistic collection of congregations, but possess a rich doctrinal treasury that will pay off in post-Christian America. This change in language and emphasis from the stage will help shift our culture, and signal what our denominational expectations and values are, particularly for Ruling Elders who drive pastoral search committees.

There is much my own Evangelical Presbyterian Church (EPC) can learn from the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA). Although the EPC and PCA hold to the same doctrinal standards, the EPC is shrinking while the PCA is growing. The EPC can learn a lot from our larger partner about how to remain faithfully confessional and missionally relevant in post-Christian America.

Broadly speaking, the PCA is the only non-Pentecostal denomination still growing in the United States. That should cause every leader in the EPC to pay attention: the only non-Pentecostal denomination still growing in America is a confessionally Reformed, doctrinally rigorous church, and it’s not us.

So, here are the usually caveats at the outset. First, while the EPC should desire for its congregations to grow and to become a bigger denomination, our first goal should be to see Christ’s kingdom grow. Second, numerous individual EPC congregations are growing and healthy and some PCA congregations are shrinking and unhealthy. But on the whole, the EPC is shrinking while the PCA is growing, and I am focused on the general contours of both churches. Third, applying principles of denominational growth to individual congregations is immensely difficult. That requires a culture shift and buy-in. Fourth, most of what makes the PCA successful required steps it took 30-40 years ago. The EPC could try and replicate the PCA’s current practices, but without a similar foundation those practices will flounder. At the same time, the EPC cannot simply duplicate what the PCA was doing from 1984-1994 in 2024; the world is different, and so the application of this foundation will by necessity look different. Long-term vision and patience are required.

Grasping the Situation

Here is the membership trends of the major (100,000+ member) Presbyterian and Reformed denominations in the United States since 2000. There are weaknesses in this table: each denomination reports membership differently (I tried to include only active, communicant membership); these numbers tend to be generated by congregational self-reporting, which can be specious; and membership does not directly correlate with worship attendance. I selected the specific years to show the collapse of the PCUSA and transfer of congregations into the EPC and ECO, as well as to highlight the pre and post-COVID states. And yes, the RCA’s numbers are accurate; in fact, their 2023 numbers are in and it’s gotten even worse.

| PCUSA | PCA | CRC | EPC | ECO | RCA | |

| 2000 | 2,525,330 | 306,156 | 276,376 | 64,939 | 211,554 | |

| 2005 | 2,316,662 | 331,126 | 273,220 | 73,019 | 197,351 | |

| 2014 | 1,667,767 | 358,516 | 245,217 | 148,795 | 60,000 | 147,191 |

| 2019 | 1,302,043 | 383,721 | 222,156 | 134,040 | 129,765 | 124,853 |

| 2022 | 1,140,665 | 390,319 | 204,664 | 125,870 | 127,000 | 61,160 |

| Change, 2019-2022 | -12.4% | +1.7% | -7.9% | -6.1% | -2.2% | -52.7% |

The PCA is the only Reformed church that has grown since 2000 without relying on transfers from the PCUSA. The PCA even had a number of disaffected groups leave it over the past few years and yet is still growing, including through COVID. The situation is actually worse for the EPC; we peaked at 150,042 members in 2016, and have declined by ~16.2% since then, while the PCA grew by 4.3% over that same period. It continues to worsen when attendance, not membership, is taken into account. The EPC’s average Sunday attendance across the denomination in 2014 was 118,947. It was down to 82,673 in 2022, a drop of a whopping 31.5%. Now, average denominational attendance is harder to measure and report accurately compared to membership, and the post-COVID practice of online “attendance” (which the EPC is trying to measure, but not well) has complicated matters. Yet the reality is clear: the EPC’s worship attendance is declining even faster than its membership. On the other hand, the PCA does not track Sunday worship attendance, but the consensus seems to be that their in-person worship attendance on Sundays is actually higher than their official membership (the OPC is on a similar path of growth and attendance as the PCA, but its total membership of 36,255 is significantly smaller).

This is not how the EPC talks about itself. We tend to talk about how much we’re growing and how the PCA is fracturing. How can the reality be so different? Regarding the PCA, the EPC has confused highly visible debates and a few departures with things going systemically wrong. Reflecting upon ourselves, the number of EPC congregations went from 182 in 2005 to 627 in 2022, but the number of congregations and pastors in the EPC has not yet declined. So the sense of growth we had from transfers in 2005-2014 has continued, even as we’ve shrunk by 25,000 members.

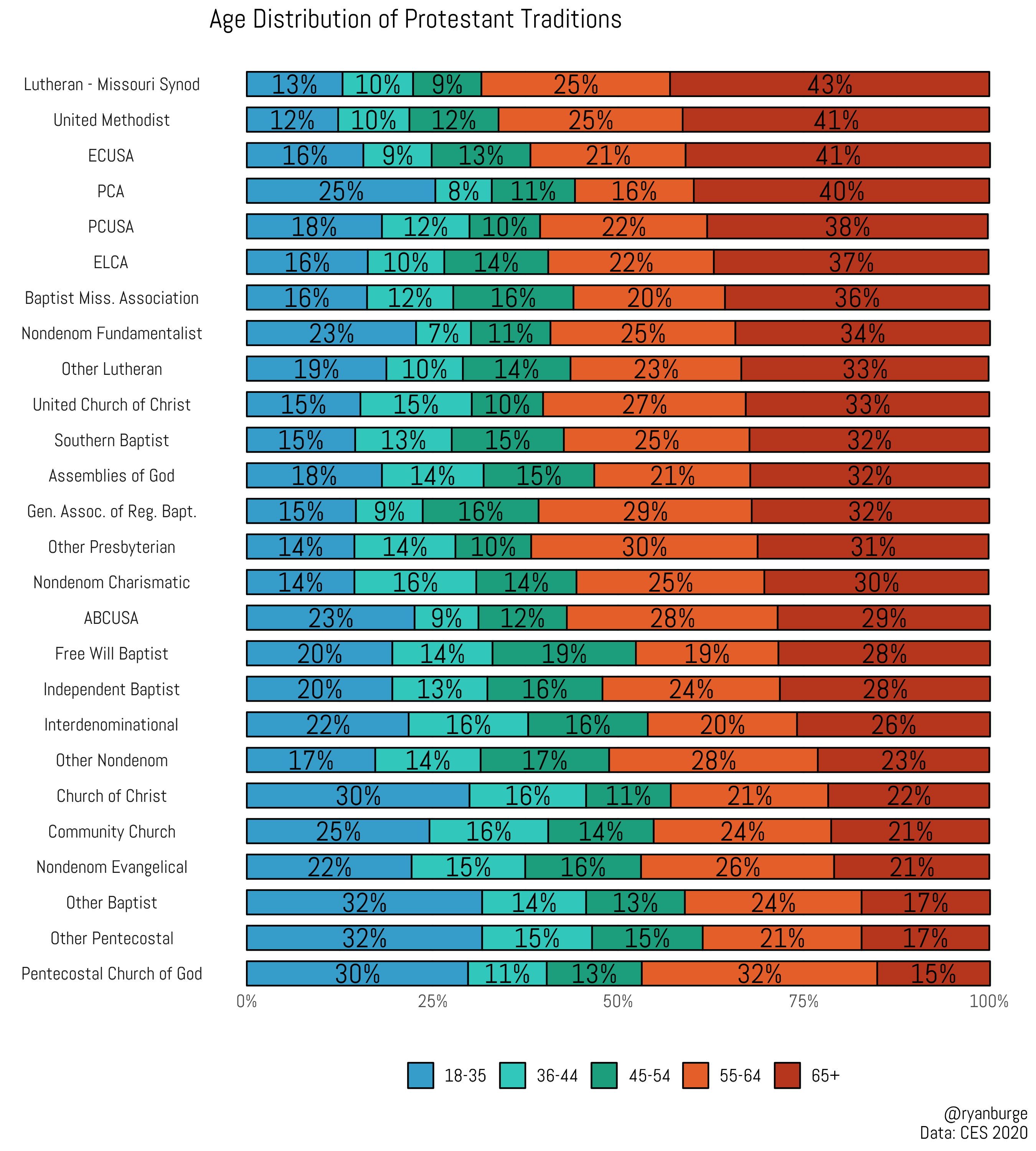

And long-term the situation is equally grim. Ryan Burge is a specialist in religious statistics, and he found that the overwhelming majority of American Protestant denominations have adult populations that are themselves majority over the age of 55 (the percentage of U.S. adults that are 55+ is about 35%), meaning that most Protestant groups are facing a demographic cliff. Pentecostals and congregationalist groups are the only churches with a majority of their adults ages of 18-54. However, the PCA just barely missed that cut, with 49% of its adult membership under the age of 55. The PCA’s 18-35 population is why: This group represents 29.4% of the U.S. adult population and 25% of the PCA’s adult membership, which are roughly comparable. The PCA is the only non-congregationalist denomination in the United States not staring at demographic extinction, and it looks to keep growing in the future.

The EPC is not big enough to make Burge’s data, but we fall into the “Other Presbyterian” category (with the CRC, ECO, and the RCA) where 62% of adult membership is over 55. This is actually worse than the PCUSA (60% of their adult membership is over 55), whose demographic demise is typically treated by the EPC as all but assured. One of the big takeaways just from looking at this data is that the massive influx of PCUSA congregations into the EPC in 2005-2014 masked that the underlying culture and demographics for many of those churches were not primed for long-term health. The EPC is essentially still the church it was in 2005: approximately 75,000 members then and 82,000 worshipers now. And it’s not like the PCA is growing by births alone; it’s averaged 5,000 adult professions of faith and 2,500 adult baptisms a year for the past 5 years. Their church planting and foreign mission ministries are also far more developed than the EPC’s.

To their credit, many of the EPC’s leaders have been trying to take steps to address this (e.g. the Revelation 7:9 initiative, the recent push for every-member evangelism, and the foregrounding of church revitalization and “next generation” ministry training). The PCA is far from perfect and is itself facing a number of challenges (e.g. engaging the working class, catching up to American racial demographic changes), though any issue they have, the EPC has worse. So, in light of the EPC’s real situation of decline and the PCA’s of growth, we should consider what we can imitate for long-term success.

Rigor and Doctrine

Both the EPC and PCA are Reformed and Presbyterian churches that affirm the Westminster Confession and Catechisms as containing the system of doctrine found in the scriptures. One thing that sets our denominations apart is that the PCA is robust about this affirmation while the EPC is minimalistic. We have the “Essentials of Our Faith”, after all. But the PCA’s confessional robustness is the primary factor in their growth. Cultivating a similar confessional rigor while maintaining our cultural ethos should be the first thing the EPC attempts in imitating the PCA.

Yes, doctrinal and confessional minimalism is a possible avenue for church growth. The Pentecostal, congregational, and non-denominational movements are all demographically viable, with non-denominational Christianity now the largest faction of American Protestantism. These groups tend to be doctrinally minimalistic. The problem is that doctrinal minimalism leads to doctrinal and cultural non-distinction: if your church tries to minimize distinctive doctrines and practices it inevitably becomes indistinguishable from broad, non-denominational evangelicalism. But as Reformed Presbyterians, we confess distinctive things. When Reformed churches downplay their Reformed distinctives, their witness, ministry, members, and children all cease being Reformed. Why attend the local EPC congregation that tries to be minimally Reformed when the local non-denominational church is exactly the same without the Presbyterian baggage? Why attend the local EPC congregation that tries to focus only on the evangelical essentials when the PCA church down the road is excited about their Reformed nature instead of minimizing it? The most famous example of this phenomenon is when the Christian Reformed Church burned their wooden shoes in the 1980s. In an attempt to go beyond their traditional, ethnic parochialism and join broader American evangelicalism, the CRC distanced themselves from their historic distinctives, and partially jettisoned their (Dutch) Reformed faith and practice along with their Dutch culture. It led to a massive numerical collapse, and the ongoing conflict in the CRC is about how to either reclaim or reframe the role of historic Reformed doctrines and practices. Reformed confessionalism and Reformed minimalism cannot coexist.

The PCA has taken the opposite tact: they have embraced and led with their Reformed values. No one is surprised about a PCA church not only affirming, but regularly teaching on predestination, unconditional election, limited and penal substitutionary atonement, monergestic salvation, the 10 commandments as God’s moral law, the regulative principle of worship, the spiritual efficacy of the sacraments, covenant theology, repentance unto life, etc. Ministry and discipleship are consciously informed by Reformed doctrinal principles, and the PCA and its congregations enthusiastically proclaim them as scripture’s testimony. And the PCA approaches this through the lens of Westminsterian confessionalism, not a reduced set of fundamental tenets. The PCA is known for its Reformed and Presbyterian distinctives. The EPC is known for letting pastors and churches disregard those distinctives.

The PCA’s ordination standards are very high. Pastoral preparation is theologically and doctrinally rigorous; in the face of growing secularization and post-Christian pressure on the church, the PCA has decided that the only way the church will remain a faithful witness is if these standards are maintained. The PCA’s expectation is that pastors are to possess biblical and theological expertise and that they are trained accordingly. Pastors are to be biblical specialists who can speak scripture to an alienated culture, and this specialization operates from a clearly Reformed and confessional vantage point. It is through this pastoral approach that the PCA’s theological culture and health is maintained.

There are many ways to assess congregational health, but the PCA first evaluates church health on confessional terms. Is the biblical gospel being preached, the sacraments being properly administered, worship being performed purely, discipline being enacted? These questions are frontloaded and never taken for granted. Other questions about evangelism, being a sticky church, mercy ministries, skill of musicians, neighborhood demographics, budgets, valorizing the past, etc., are secondary. Those are important topics, but don’t supersede (by either commission or omission) the bigger doctrinal categories; the same cannot be said for the EPC at this moment.

The missional fruit for the PCA is clear: by being center-bounded on a robust confessional system for their pastors and churches, the PCA has successfully adapted to our culture and built healthy congregations without losing their Reformed distinctives. It may seem odd from an EPC perspective, but the PCA’s stricter approach to Reformed theology has granted them greater flexibility; having a broader foundation and knowing their center clarifies their missional parameters.

Subscribe to Free “Top 10 Stories” Email

Get the top 10 stories from The Aquila Report in your inbox every Tuesday morning.