Approximately 40 lines out of ~20,000 lines in the New Testament text are in doubt, mostly the longer ending of Mark’s Gospel and the first 11 verses of John 8. So, the total number of seriously disputed lines in the New Testament is less than 1/2 of 1% of the total text. The New Testament text is 99.5% reliable, based on the comparison of thousands of manuscripts from three different continents over 15 centuries. But what about the disputed .5%? Surely that’s where all of the core Christian doctrines are, right? Wrong. There is not a single Christian doctrine of any kind that is affected by these disputed lines of text. Not one.

This is Part 2 of a 3-part series of posts on the reliability of the four New Testament Gospels. (Part One; Part 3) In our last post, we considered the question of why these four Gospels. Now, I want to move on to the second question: Aren’t these Gospel full of errors?

It’s become very commonplace to say that the Bible is full of errors and full of contradictions. It’s almost accepted as widely know fact. Skeptical scholar Bert Ehrman has even made reference to hundreds of thousands of errors in the manuscripts of the New Testament. Let me take a minute to explain the manuscripts of the New Testament and then deal with the issue of errors (mistakes, problems within each Gospel text) and next time we’ll deal with contradictions (conflicts between the recorded information in the different Gospels).

In dealing with errors in this post, I want to address both textual errors (mistakes in the manuscript) and historical/factual errors (supposed mistakes in the teachings/assertions of the Gospels):

Manuscripts and Textual Errors:

Ancient manuscripts were copied by hand. This is true of everything written before the invention of the printing press in 1439. Hand-written manuscripts also don’t last forever, especially if they are used. Thus, everything we have from the ancient world, anything written before ~1500 relies on manuscripts, hand-written copies of copies for its text.

So, how do we know for sure that anything we have from the ancient world is reliable? This is not just a problem for the Bible but for all ancient writings. Well, three factors boost our confidence in the reliability of ancient manuscripts:

1. When we have more manuscripts, so we can compare them with each other

2. When we have early manuscripts close to the date of the original writing

3. When we have a diversity of manuscript traditions – in other words, different copies of different manuscripts in different areas not influences by each other.

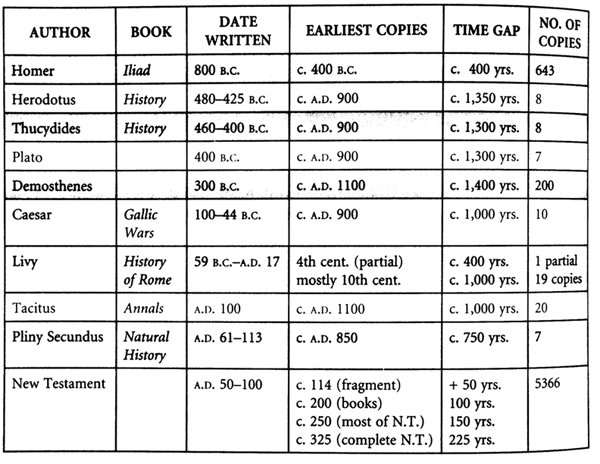

So, let’s quickly compare the New Testament manuscripts to other manuscripts of writings from the ancient world: Outside of the New Testament, the best-attested, most-supported ancient writing is probably Homer’s Illiad. We have 643 manuscripts of The Iliad, the earliest dates to around 400-500 years after Homer wrote the epic poem. On the other hand, we have over 5,000 complete manuscripts of the New Testament (over 24,000 total manuscripts), and the earliest dates to within 50 years of the writing of the original (a fragment of the Gospel of John which dates to ~125).

Here is a chart to compare other ancient writings and their manuscripts, taken from Josh McDowell’s book, Evidence That Demands a Verdict:

The impressive set of New Testament manuscripts is not just a matter of volume, though. We also have great diversity, with manuscripts in several different ancient languages besides the original Greek and Greek manuscripts from a diversity of geographical areas and manuscript traditions. Specifically, New Testament manuscripts can be grouped into four major text traditions on three different continents. This geographical, cultural and text-tradition diversity makes it impossible that church leaders could have conspired together to make the manuscripts match each other.

Now with this large number of hand-written manuscripts in so many diverse locations, scribal errors are inevitable. No matter how carefully something is copied by hand, mistakes will be made. Bart Ehrman and other scholars have made lots of money and generated lots of publicity pointing out hundreds of thousands of textual errors in the New Testament manuscripts. Well, Ehrman is right. The whole volume of 24,000+ New Testament manuscripts with millions of words in them are bound to have a large number of copying errors.

But what kind of errors do we see in the manuscripts? Almost all of them are spelling mistakes or what we would call “typos” today. These have absolutely no bearing on the meaning or substance of the text at all. It’s like this:

1. When copying a manuscript by hand, numerous errors can be made without changing the text.

2. When copying a manuscrpt by hand, numerous errrs can be made without changing the text

3. Whin copying a manuscript by hand, numerous errors can be made without changing the txt.

4. When copying a manuscript by hand, numerous errors can b made witht changing the text.

5. When copying a manuscript by hand, numerous error can be mede without chanjing the text.

The next largest category of errors in manuscripts are grammatical or syntax errors, where a scribe, perhaps not fluent in Greek himself, makes a mistake that changes the grammar in a way that doesn’t change the text. For example, I might writes something not correctedly and the meaning of that somethings are still clearer.

Once you get beyond these meaningless errors, you do come to a number of differences between the texts that do have some substance to them. Comparing these to each other, you sometimes find a word or two or a brief expression that might be one way or the other. Most of these are so small and so insignificant as to be pretty close to meaningless.

So, when all is said and done, how much of the New Testament has serious doubt as to its accuracy? Is it more or less 10%, do you think? Actually, far less! Approximately 40 lines out of ~20,000 lines in the New Testament text are in doubt, mostly the longer ending of Mark’s Gospel and the first 11 verses of John 8. So, the total number of seriously disputed lines in the New Testament is less than 1/2 of 1% of the total text. The New Testament text is 99.5% reliable, based on the comparison of thousands of manuscripts from three different continents over 15 centuries.

But what about the disputed .5%? Surely that’s where all of the core Christian doctrines are, right? Wrong. There is not a single Christian doctrine of any kind that is affected by these disputed lines of text. Not one.

So, textually, we have a reliable New Testament. But what about historically?

Ancient History and Historical/Factual Errors:

I’m going to answer this one much more briefly and then direct you to resources for further study. In short version, beware of anyone who criticizes the historical reliability of the Bible based on what “we know” from the ancient world. Our knowledge of the ancient world is incomplete, fragmentary, biased and contradictory.

So what do people challenge? Everything, which is why I can’t address it all here. You’ll hear everything from assertions that Luke’s reference to a census while Quirinius was governor of Syria is wrong [something we still don’t fully understand] to an assertion that Jesus was not crucified because we have no record of His crucifixion under Pontius Pilate [as if we have such complete records] to an flat-out denial that Jesus ever lived [which is ludicrous but growing in popularity]. In short, you can find people who will challenge almost everything the New Testament says and say vague things like “We know . . . ” and “Based on our knowledge of the ancient world, we can say . . . ” Just beware of these kinds of statements.

Nothing the New Testament asserts as a historical fact has ever been definitively disproven. On the contrary, the New Testament, and the Gospels in particular, provide us with an incredibly accurate, detailed historical context for the life of Jesus. The details of life under Roman occupation, life in first century Israel, etc. all ring true with what we have from other ancient writers, like Josephus. Moreover, Luke especially is careful to give us precise historical references so we can place the events of the Gospels in history, not in mythology.

Jason A. Van Bemmel is a Teaching Elder in the Presbyterian Church in America. This article appeared on his blog Ponderings of a Pilgrim Pastor and is used with permission.

Subscribe to Free “Top 10 Stories” Email

Get the top 10 stories from The Aquila Report in your inbox every Tuesday morning.